|

To follow along on the political education call on Racism 101

(February 2017), download this file - you can download it as a Powerpoint or a .pdf file. You can also listen to the audio for the call here.

Understanding RacismRacism is a word that is widely used and yet often carries many different meanings depending on who is using it. If we want to work together effectively for racial justice, and we do, we need to be clear about what racism is, how it operates, and what we can do to end it.

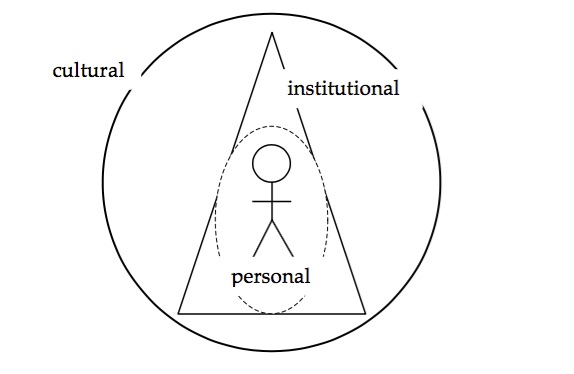

We define racism, also referred to as white supremacy, as the pervasive, deep-rooted, and longstanding exploitation, control and violence directed at People of Color, Native Americans, and Immigrants of Color that produce the benefits and entitlements that accrue to white people, particularly to a white male dominated ruling class. Often white people think of racism as prejudice, ignorance, or negative stereotypes about People of Color. This definition often leads to the assumption that the solution to racism is to challenge misinformation about People of Color or other marginalized groups or to convince white people to be more tolerant or accepting. In fact, prejudice, ignorance, and stereotypes are the result of racism, not the cause. Every one of us in this society, growing up with the lies, misinformation, and stereotypes found in our media, textbooks, and cultural images and messages, carries deep-seated and harmful attitudes towards many other groups. It is our responsibility, as people with integrity, to unlearn the lies and misinformation we have learned and to replace them with more truthful and complex understandings of the peoples and cultures around us. Racism operates on three different levels and it is important to understand each of them and their interconnections. |

This short video frames the construction of whiteness as a tool of divide and conquer.

| ||||||||||||

Interpersonal

|

Institutional

|

Structural

|

Discussion QuestionsWhat are a couple of examples of interpersonal racism that you have seen personally or heard about from the media recently?

What harm do they do? What are a couple of examples of institutional racism in our society? What harm does institutional racism do to People of Color? How does it benefit white people? What are examples of structural racism—the interplay between different forms of institutional and interpersonal racism? What are examples of cultural racism that you have seen recently? What do you imagine is their cumulative impact on People of Color, Native Americans, and Immigrants of Color? What do you see as their cumulative impact on white people—what attitudes and expectations do they produce in us? What do you think needs to be addressed to stop these and other acts of violence against People of Color, Native Americans, and Immigrants of Color? |

The 3 Expressions of Racism: Another way to think about racism as more than personal is to understand that personal racism (individual acts of meanness) occurs within institutions. The policies and practices of those institutions in their turn are disproportionately serving and resourcing white people while underserving and exploiting People of Color. This institutional racism reproduces itself within a culture that tells us that white people are smarter and more qualified while People of Color are undeserving. From dRworks workbook - www.dismantlingracism.org.

|

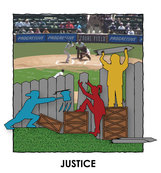

STRUCTURAL RACISM: The Unequal Opportunity Race

This 2010 video was produced by the African American Policy Forum (AAPF) to highlight the historical and structural barriers that create inequity based on race. The video builds on President Lyndon Johnson's point that: “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still believe that you have been completely fair.” The video draws attention to both the disadvantages of having to run in lanes shaped by racial inequality, and the advantages that accrue to those who do not confront such obstacles. |

Paul Kuttner offers some insight into the much used graphic that attempts to illustrate the difference between equality and equity. Take a look here. |

Links

Another way to think about how racism operates can be explained through

the 4 I's of oppression: internal, interpersonal, institutional, and ideological.

the 4 I's of oppression: internal, interpersonal, institutional, and ideological.

|

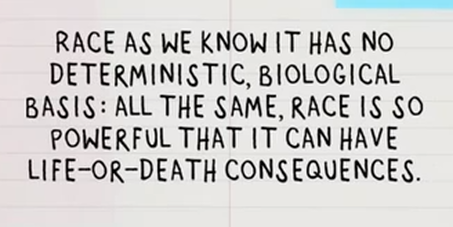

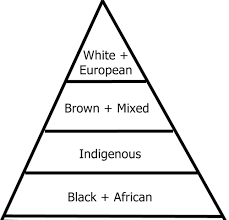

Race is not scientifically or biologically "real." Race was constructed for social and political purposes. Race was constructed as a hierarchy and not as a multicultural "salad" or "soup." In other words, race was constructed in order to reinforce the idea that "white" is superior and at the top of the hierarchy, that "Black" is inferior and at the bottom of the hierarchy, and that all other constructed racial categories move up and down between those two anchors depending on what is happening at any given moment in our history. For example, before 9/11, many Arab Americans were considered closer to white; now, as a result of U.S. foreign policy and rising Islamophobia, the racial category of "Arab" is considered closer to the bottom. White supremacy refers to the ideology or belief system that this pyramid or hierarchy suggests - the idea that white is superior, better, more while all other races are inferior, worse, less. White supremacy is reflected in individual beliefs, in institutional policies and practices, and in our cultural assumptions about who is deserving and who is not. We do not have to be members of the Ku Klux Klan to be participating in white supremacy.

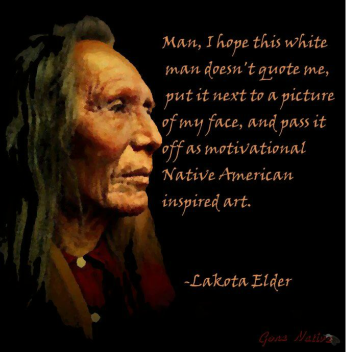

For more about the construction of race and its consequences, visit Race: The Power of an Illusion website. Cultural Appropriation

|

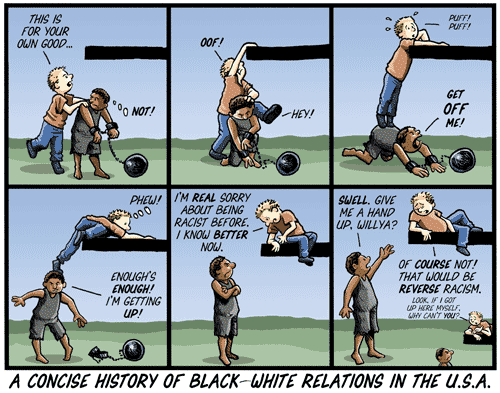

A Short History of Racism

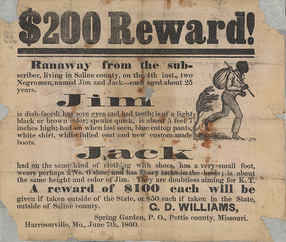

The origins of racism in western societies is deep and complex. Legal and political racism in what was to become the United States started to take root in the early 1700s in the mid-Atlantic coast British colonies. Until that period, Europeans, Native Americans and Africans often worked and lived together in shared circumstances of servitude. They also resisted and rebelled together against the way they were treated.

As early as 1640, however, before the word "white" ever appeared in colonial law, the colonial courts began to make racialized distinctions that set up white privilege. One of the earliest examples of the establishment of white privilege involves three servants working for a farmer named Hugh Gwyn; the three servants attempted to run away to Maryland. In the records from the case, one was described as a Dutchman, the other a Scotchman; the third was described as a Negro. They were captured in Maryland and returned to Jamestown, where the court sentenced all three to 30 lashes -- a severe punishment even by the standards of that time. The Dutchman and the Scotchman were sentenced to an additional four years of servitude. The black man, named John Punch, was ordered to "serve his said master or his assigns for the time of his natural Life here or elsewhere."

This court ruling reflected the reality that the landowning class in Virginia and the other growing colonies was heavily outnumbered by the growing numbers of Europeans coming as indentured servants, the growing numbers of Africans being forcibly brought to work the land, and the large numbers of Indigenous peoples and communities being slowly and relentlessly moved to make way for colonial settlement. The attempted escape of Hugh Gwyn's three servants was one of many such attempts, large and small, by those facing shared servitude and exploitation. In response, the landowning class in Virginia began to pass laws and create policies like the 1640 case of John Punch. These laws and policies were explicitly designed to "divide and conquer." The weapon of choice was racism -- designating "white" as a legal category and introducing the concept of life-long servitude (slavery) as distinguished from shorter-term servitude (indenture). The landowning elite constructed race and racism as a tool of control, persuading poor and working class European immigrants to give up their language and customs, assimilate into whiteness, and ignore their economic and social common ground with peoples brought from Africa into slavery and Indigenous peoples being forced off their land.

By the 1730s, legal and social racial divisions were firmly in place. Most Black people brought forcibly from Africa and their descendants were enslaved and even free Black people had no right to vote, bear arms or bear witness in court. Black people were also barred from participating in many trades during this period. Meanwhile, whites gained the right to corn, money, a gun, clothing and 50 acres of land at the end of their indentureship; often "free" white men found paid work in the capture and control of runaways and Indigenous peoples. In other words, poor whites “gained legal, political, emotional, social, and financial status ... directly related to the ... degradation of Indians and Negroes.”

Although poor whites gained some economic benefits over enslaved and Indigenous peoples, the increased productivity from slavery widened the gap between wealthy whites and those who were poor. The legacy of this history is evident today; although the wealth gap is larger than it has ever been in our nation's history, the politics of racial divide and conquer are disturbingly alive and well.

As early as 1640, however, before the word "white" ever appeared in colonial law, the colonial courts began to make racialized distinctions that set up white privilege. One of the earliest examples of the establishment of white privilege involves three servants working for a farmer named Hugh Gwyn; the three servants attempted to run away to Maryland. In the records from the case, one was described as a Dutchman, the other a Scotchman; the third was described as a Negro. They were captured in Maryland and returned to Jamestown, where the court sentenced all three to 30 lashes -- a severe punishment even by the standards of that time. The Dutchman and the Scotchman were sentenced to an additional four years of servitude. The black man, named John Punch, was ordered to "serve his said master or his assigns for the time of his natural Life here or elsewhere."

This court ruling reflected the reality that the landowning class in Virginia and the other growing colonies was heavily outnumbered by the growing numbers of Europeans coming as indentured servants, the growing numbers of Africans being forcibly brought to work the land, and the large numbers of Indigenous peoples and communities being slowly and relentlessly moved to make way for colonial settlement. The attempted escape of Hugh Gwyn's three servants was one of many such attempts, large and small, by those facing shared servitude and exploitation. In response, the landowning class in Virginia began to pass laws and create policies like the 1640 case of John Punch. These laws and policies were explicitly designed to "divide and conquer." The weapon of choice was racism -- designating "white" as a legal category and introducing the concept of life-long servitude (slavery) as distinguished from shorter-term servitude (indenture). The landowning elite constructed race and racism as a tool of control, persuading poor and working class European immigrants to give up their language and customs, assimilate into whiteness, and ignore their economic and social common ground with peoples brought from Africa into slavery and Indigenous peoples being forced off their land.

By the 1730s, legal and social racial divisions were firmly in place. Most Black people brought forcibly from Africa and their descendants were enslaved and even free Black people had no right to vote, bear arms or bear witness in court. Black people were also barred from participating in many trades during this period. Meanwhile, whites gained the right to corn, money, a gun, clothing and 50 acres of land at the end of their indentureship; often "free" white men found paid work in the capture and control of runaways and Indigenous peoples. In other words, poor whites “gained legal, political, emotional, social, and financial status ... directly related to the ... degradation of Indians and Negroes.”

Although poor whites gained some economic benefits over enslaved and Indigenous peoples, the increased productivity from slavery widened the gap between wealthy whites and those who were poor. The legacy of this history is evident today; although the wealth gap is larger than it has ever been in our nation's history, the politics of racial divide and conquer are disturbingly alive and well.

LINKS to resources that go deeper into the history

|

|